Mank

In 1940s Hollywood, up and coming director Orson Welles has been given carte blanche by RKO studios to develop whatever film he wants. With this is in mind, he settles upon veteran screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz to write the script. ƒmank

Secluding Mankiewicz in Victorville, California under the watchful eye of producer John Houseman, Welles expects great things of Mankiewicz or “Mank” as he’s more commonly known. However as well as being a gifted writer, Mank is also a functioning alcoholic and with only 90 days to turn in the script of the century, no one really knows if he’s going to deliver. Not even Mank himself.

… “what god would have built, had he’d the money.”

Opening in gorgeously grainy black and white, Mank is a film as much steeped in references as it is with reverence. Essentially the dramatised series of events that led up to the creation of Orson Welle’s seminal Citizen Kane, director David Fincher layers the screen with a multitude of clues and subtle visual motifs that hint at the kind of film that Citizen Kane will eventually become.

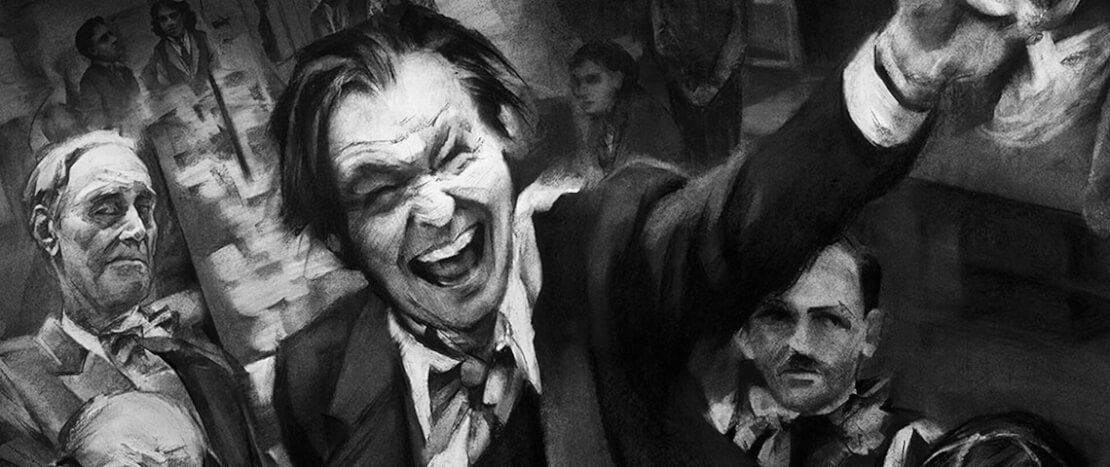

Set in the centre of the movie though, is the performance of Gary Oldman as Mank himself. A stone that seems able to skip on the surface of any social pond, both character and actor are in a pretty unassailable position. Mankiewicz is revered by his peers as a touchstone writing talent and Gary Oldman has made a career of effortlessly disappearing inside his onscreen characters, making both preternaturally disposed to each other. Add to this also the reputation of Citizen Kane itself being a film so ridiculously far ahead of its time, and you have a prequel that Mankiewicz may have described as being “what god would have built, had he’d the money.”

Fortunately though, Mank is not a film dependant upon a deep and thorough advance knowledge about Citizen Kane or its infamous inspirations. What it is, is a film about gambling because, at its heart, both Mankiewicz and Welles are risk-takers. In thumbing his nose at the Hollywood establishment, Mank will risk everything to what write about what he knows – power.

In doing so, the film darts backwards and forwards through time, itself aping the non-linear style of Citizen Kane. Careening from one scene to another, as if sobriety is a virtue best avoided, Oldman’s Mank skewers the vanities of studio bosses and starlets alike all the while being watched on by their ringmaster, newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst. Wallowing in the shadows and hooded by Charle’s Dance’s expertly expressive eyes, both hunter and quarry recognise each other, yet whilst imagining each in different roles. Mank is no threat to Hurst and Hurst is a target too big for Mank to ignore, and so the stage is set for what becomes an increasing trial of nerve.

With their bugles wheezing and ponderous fingers tripping down a piano keyboard, musicians Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross beautifully light the way. With Mank’s target now fully exposed to the gossiping of Hollywood’s glitterati, Fincher moves his lovingly made prequel into high gear. -Will Mankiewicz get away with it, and if so, will he receive the credit he’s due if he does? Irrespective of whether history chooses to see either Welles or Mankiewicz as organ grinder or monkey, Fincher’s delivers a witty truth that both were needed for what would be the takedown of the century.

Wisely keeping Tom Burke‘s appearances as Orson Welles to an absolute minimum, Mank is a film that will be as memorable for Gary Oldman’s descent into character as it will be David Fincher’s expert cutting of Mank’s heartstrings.